Sean McCormick was way ahead of his time—25 years to be exact. That’s when the entrepreneur, a member of the Métis Nation, founded Manitobah Mukluks, makers of handmade winter boots that Indigenous people living in the Canadian Arctic have been wearing for 10,000 years. And while making a style that’s been around for millennia isn’t visionary, McCormick’s business model is—namely, a strong social impact component that has been a cornerstone of operations since day one.

“We’ve created a unique and forward-thinking model that combines traditional business metrics for success with a meaningful social impact component,” McCormick says. “They’re completely entwined; it’s part of our corporate DNA.”

The result is a form of effective altruism, which is defined as a social movement aimed at benefitting others as much as possible. Companies that put people and concerns like protecting the environment above profits, or at least on equal footing, are part of this burgeoning movement. But back when Manitobah Mukluks (now shortened to Manitobah) debuted, McCormick’s intentions were more limited in scope. The young exec, who sold leather and fur during high school and later established a trading post where Indigenous artisans could trade their handmade mukluks and moccasins, envisioned broader market potential for such goods, but also just wanted to do some good for his people. Little did he foresee how his business model—which he calls “kinder capitalism”—would flourish. It’s now at the forefront of a movement that has inspired many companies, across all industries, to model/remodel themselves. That is what makes McCormick a visionary.

“The bigger our brand gets, the more social impact we get to make with Indigenous communities,” McCormick says. “And the bigger the impact, the bigger our brand gets because that aspect is resonating with consumers more than ever.” He adds, “We’re pioneering this model, and more and more companies are realizing that they have to be a force for good and positive change, which we welcome.”

McCormick stresses, however, that Manitobah isn’t a charity. About half of its employees are Indigenous. The company also operates the Indigenous Market, an online marketplace featuring one-of-a-kind mukluks made by Indigenous artists (for upwards of $1,500) and other handcrafted accessories; 100 percent of the revenue goes to the artists. “This can change an artist’s life,” McCormick says. “We aren’t just cutting a check to some charity at the end of the year based on some preconceived notion that it’ll make us look good. Our social impact is built into our business model in a way that pays dividends to the owners, shareholders, employees and Indigenous communities at large.”

Indeed, Manitobah isn’t built like most companies. For example, many would take a cut of those online marketplace sales. But that’s not how Manitobah rolls. “We’ll never compromise on our roots—just as we wouldn’t compromise on making great product, being data driven and consumer centric,” says McCormick, noting that the company is indebted to the Indigenous people who invented mukluks. “If we don’t pay back the debt every day, then we really don’t have license to keep selling mukluks. As long as we honor that commitment, I believe we can run a for-profit business with fantastic metrics on both sides of the ledger.”

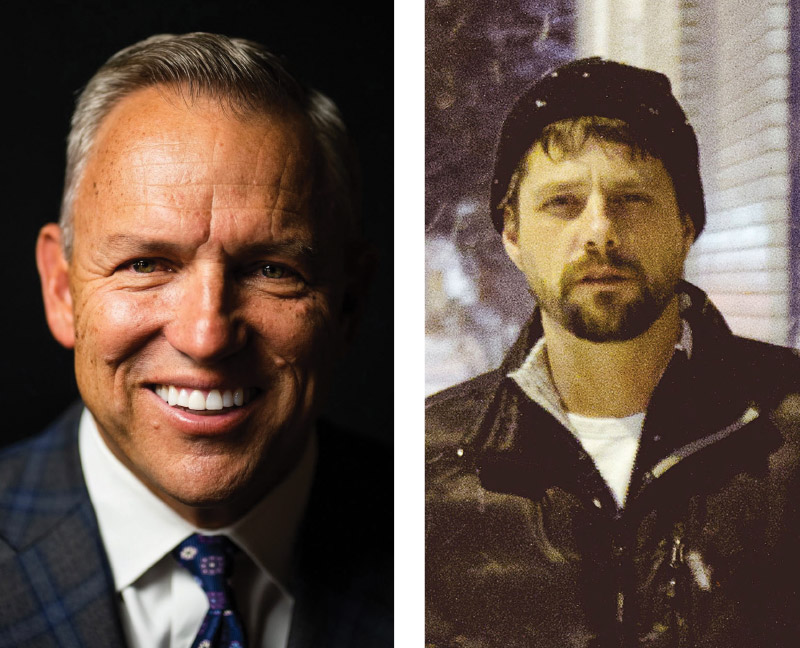

Manitobah’s unique makeup caught Greg Tunney’s attention in early summer 2021. The industry veteran had just come off a three-year stint as Global President at Wolverine Worldwide and was working with an East Coast–based private equity firm on potential footwear acquisitions. When Manitobah came across his desk, Tunney was somewhat familiar with the brand, but a deeper dive convinced him of much bigger potential. “I’d been looking at about eight pitch decks and this wasn’t the biggest or the smallest, but there was something there,” says Tunney, who took it to Seattle-based Endeavor Capital after the original equity group got cold feet during the pandemic. Endeavor saw big potential. They struck a deal, and Tunney became CEO that November while McCormick embraced a new official role as Chief Impact Officer.

What did Endeavor and Tunney like about Manitobah, specifically? “First and foremost, it’s an extremely authentic brand,” Tunney says. “Secondly, its social impact DNA was something we’d never seen before and believed could be built upon because that aspect increasingly resonates with Gens X, Y and Z.” Last but not least, he cites Manitobah’s untapped lifestyle brand potential. “This is much bigger than just a shoe brand,” Tunney says. “It’s an amazing brand story that also resonates globally.”

McCormick knew he needed support to help his baby reach its full potential. Like many entrepreneurs, he was running on fumes after decades serving as CEO, COO, warehouse staff—whatever it took to keep his dream alive. He also needed industry expertise to take Manitobah to the next level. “Being an entrepreneur is one thing,” McCormick says. “Building a global brand is another.”

But McCormick wasn’t seeking just any partner. Both Tunney and Endeavor had to embrace Manitobah’s raison d’être. “What resonated most with Greg and Endeavor is they got what Manitobah is all about,” he says. “Without that, I couldn’t have cared less about their CVs. We’re convinced that Greg has the chops, passion and understanding to lead us to our full potential.” The admiration is mutual. “Sean is so ahead of his time on social impact but, at the same time, he’s the most entrepreneurial and capitalistic guy I’ve ever met,” Tunney says. “I’ve been a brand guy for 30 years, yet Sean’s understanding of what a brand can be is so far ahead of mine.”

Year one of the new team is now in the books, and Tunney and McCormick couldn’t be more pleased with the rapid progress made on all fronts. Highlights include opening five brand-immersive flagships across Canada; an expanded product offering including the first-ever women’s sandal and men’s collections for Spring ’23 and Fall ’23, respectively; a profile in Fortune magazine and plenty of other press coverage; U.S. ecommerce sales up 38 percent; becoming EDI compliant; opening three new warehouses; and partnering with a highly selective account list that includes front table displays in Nordstrom and Dillard’s locations. “If I’d told Sean and Endeavor that we’d achieve all that in our first year, I think they’d have thought I was crazy,” Tunney says. “Amid a very challenging market, our stores are running 41 percent over plan—all at full price. Overall, it’s been far beyond my expectations.”

McCormick, too, is thrilled. “We’ve easily done more impact this year than any year in our history, which is very rewarding,” he says. “It’s what Greg and Endeavor promised me the opportunity to do, and that’s great for me, the brand and Indigenous communities.”

What does it take for an altruistic business model to be successful on a global scale?

SM: Authenticity, for starters. I grew up wearing mukluks, and my grandfather wore them. He was a trapper and had a sled dog team. So, not only are we selling what I know is historically the best winter boot with 10,000 years of history behind it—plus a bunch of other great products—our consumers can bring about positive change with their purchases. They’re joining our mission, as well as benefiting emotionally and physically by buying the best footwear.

Is Manitobah at the forefront of a new model of capitalism?

SM: Absolutely. Our social impact is entwined within our company, and it’s authentic. I attribute a lot of our success to the fact that consumers can sniff out a fake. We’re the opposite of that. However, you still have to make money, which I tell our team all the time. That’s why we judge our social impact metrics the same way we do the business side. Both sides must be held accountable. That said, consumer metrics reveal that our good corporate citizen aspects are rewarded by consumers. People are busy and have their own struggles, but they do want to make the world a better place, and this is an easy way for them to do it—and keep their feet warm. I don’t think it’s any more complicated than that sometimes. Also, just because you’re in business doesn’t mean you have to leave your morals at the door.

GT: I think Sean was 25 years ahead of the entire marketplace when he came up with this business model and realized, right away, the importance of it. He believed it would have stickiness and consumers from around the world would increasingly come around to it. For example, our social impact response on our ecommerce site in the U.S. is stronger right now than in Canada and a recent NPD report cited that 83 percent of Gen Xers as willing to pay full price for a social impact brand. That figure rises for younger generations. This movement is real, and it’s a business model that effects the bottom line and allows us to do more social impact.

Playing devil’s advocate, will the majority of public company shareholders be okay with giving up potential earnings for social impact causes?

GT: Maybe not in my lifetime. (Laughs.)

SM: If you ask young and future consumers who they’ll support, it’ll force companies to act in this manner. Younger generations are demanding more from the brands they purchase. I also believe you can make a social impact without having to chop profits in half. That’s a misnomer. For example, we now work with a fair-trade certified footwear factory in Vietnam. Maybe they make eight percent profit instead of nine, but they attract more people, have greater staff retention, the production quality is better and they probably make more money overall. I’ve seen that in action with Manitobah. We wouldn’t have had our level of success without our social impact component, focus, belief and purpose. I don’t think doing the right thing and making a profit are mutually exclusive. Going forward, I believe this combination is going to become the norm. Greg is a healthy guy, so I do think it’ll happen in his lifetime. But it’s a process, for sure.

GT: Helping that process is Sean having picked the right partner in Endeavor. They’re different than most private equity firms. They didn’t buy the company and immediately put a bunch of debt on the balance sheet, like many other firms do. They’re focused on what the brand is about and investing in its full potential. They’re also typically longer-term holders; more like seven to nine years. They aren’t just looking to flip it.

Could Manitobah become or join a public company one day?

GT: Sure. There are already a few private equity groups solely focused on this social impact model. I also think there will be public companies dying for our expertise in how to run this business model. Most don’t have a clue how to go about it. A recent example is when Merrell ran an ad in support of George Floyd. Good intentions, but social media quickly called them out for not employing many Black people. The idea that brands can jump onto whatever the trend of the day is has risks. If the cause isn’t part of the brand’s DNA, consumers will smell it a mile away. Fortunately, our team lives and breathes our brand’s social impact DNA every day.

Does Manitobah have year-round sales potential?

GT: Absolutely. We’re bringing in our first sandals collection this spring, and the response has been terrific. We didn’t go the me-too route, for starters. Our collection is designed and handmade by Indigenous artists in Léon, Mexico. Dillard’s and Sundance said it isn’t something that they already planned to carry, which is great news. Beyond that, Sean’s global vision invites and collaborates with all Indigenous people. That includes potentially over 600 tribes in the United States, 200-plus tribes in Canada and many others elsewhere around the world.

SM: There are lots of Indigenous communities that only wear what we call spring/summer footwear. Certainly, in South and Central America, but it also gets into the 90s on the Canadian Prairies. They aren’t wearing mukluks year-round. So, there’s lots of inspiration for warm weather Indigenous designs from just this region of the world. But there really is no end to the history and artistry we can draw from Indigenous people here and elsewhere.

How is Manitobah different from, say, Ugg or Merrell?

GT: That’s a good question, and I’ll start by saying those brands are part of Delaware incorporated companies, which is no different than us. But in their articles of incorporation, the first sentence states that the corporation is set up for the benefit of shareholders. Manitobah’s states that our primary focus is to shareholders and our social impact efforts, which is an absolutely different dynamic than those brands.

What is Manitobah’s distribution strategy?

GT: For starters, if a retailer wants to buy a boot from us and merchandise it on the back shelf, that’s not going to fly. Our retail partners must carry an assortment, including a table dedicated to Manitobah in front, so people can discover our brand. Retailers also have to let us come in with our activation, which includes Indigenous dancers, musicians and artists to let consumers engage with our brand. Any retailer we partner with must meet that commitment. We’ve already scaled our account list in Canada from 500 to 600 to about 150 because of that. Now as we open REI this fall, I suspect we’ll have a lot of outdoor specialty stores come to us, but it will come down to whether they have the capacity to treat our brand the way it needs to be. Otherwise, it won’t be successful for us. I learned that lesson from David Kahan when he took over Birkenstock in North America. When he started, the brand was basically a couple of styles on the back shelf where the old hippie customer would come in for his repeat purchase. David said no more. Either we’re represented in stores properly, or not represented at all. I agree.

If a style looks to be the next Ugg Classic Short, would you go to a factory in China and crank out production?

GT: No, and the reason we can’t, for starters, is we don’t manufacture there. We’re in socially conscious factories in Vietnam, Mexico and Canada. But I couldn’t do it, even if I wanted. We have a whole vetting process we must go through first regarding design, development, marketing, ecommerce, physical stores, etc. It all must be approved by our social impact team to ensure its culturally correct. Even if it’s a potential huge money maker, if it doesn’t line up with our core values, we’re not allowed to do it.

SM: Every product we make has an Indigenous benefit to it, whether that’s to the artist who designed the bead pattern or to the people working in our offices and retail stores. Everything we do must have a social impact component built into it, or we won’t do it.

What is Manitobah’s biggest challenge right now?

GT: Educating consumers to bring our awareness up. Fortunately, I’ve never met anybody yet who says, ‘Nice story, but I’m not interested.’ Once they hear our story and plan, they immediately want to be part of it. When I first met with Nordstrom and Dillard’s, being a shoe guy, I was focused on showing product. But they were just as interested in our social impact efforts and wanted to learn more about it. Don’t get me wrong, the product has to be right, but we’re finding U.S. retailers are equally interested in our social impact efforts. That blew me away initially, but when I thought about how the Métis people had been brought near to extinction, I believe there’s a calling, whether you’re Canadian or American, that this needs to be righted. Now, growing up did I ever think there’d be an Indigenous month in the U.S.? Are you kidding me? But times change. There’s a swell of social awareness among people who want to be a part of and give back to meaningful causes. Manitobah, in that regard, isn’t just a transaction, like I think most labels today are. Consumers are looking for so much more than that. They want interaction and authenticity, and they want to make a difference.

What are Manitobah’s key goals for this year?

GT: This past year was a test and learn process in a lot of areas, like our stores. The results there tell us that we’ll definitely add more locations going forward. I’m going to Banff this month where there’s a Canada Goose store doing $12.5 million annually. The owners have heard about our stores and asked us to visit to look at some properties. Our goal is to identify key destinations of experience, whether that’s Banff, Whistler, Jackson Hole Park City, etc. Places where people can experience the brand in our environment and learn about our Indigenous community. We envision adding three to five stores annually. Other focuses include DTC and growing in the U.S. market, which is untapped. That includes select partners, like Nordstrom, Dillard’s and Zappos, who are already on board, and soon REI. With regard to the latter, our boots are beautiful pieces of art, but also perform. They’re waterproof, warm in Arctic conditions and feature Glacier Grip on the outsoles. That’s a key factor in REI’s decision bringing us in as a major program. There are also new retail partners, like Simon’s in Canada. They’re like the mini Barneys there. Strategic urban areas are another distribution focus, which can be addressed by our existing partners as well as select independents.

SM: On the social impact front, we’ll be publishing our first annual report. Historically, we haven’t done the greatest job tooting our own horn, so we’re going to promote a lot of the good deeds we’ve done this past year. We’re also putting playbooks in place to make sure our organization remains Indigenous-focused. For example, we support the Manitobah Mukluks Storyboot School, which teaches Indigenous and non-Indigenous kids how to make mukluks and about Indigenous culture and knowledge. We’re rolling out a digital archive curriculum where we’ll be able to reach thousands of kids across North America starting this year, which is exciting. We’ve also set aggressive growth goals for our Indigenous Market. There’s lots to keep busy.

What do you love most about your jobs?

GT: First, I love working with entrepreneurs. I’ve been fortunate to work with Tina Valdez at Foot Petals and Dixie Powers at Baggallini while I was CEO of RG Barry, as well as with Harrison Trask (founder of H.S. Trask) when I was with Phoenix Footwear Group. They put their entire lives into their companies and did everything to make their dreams happen. I loved working with them on those journeys, just like the one I’m on now with Sean. Secondly, I love that we’re a work-from-home-first company, which allows us to attract some of the finest talent in the world. My design team is based in Boston, my marketing head is in San Francisco and I’m based in Park City, UT. Throughout my career, I’ve moved around the country to pursue opportunities, but I’m at a point now where my wife said it’s okay to move for another opportunity, but she’s staying in Utah. The world has changed dramatically, though. In order to get talent, this model works best. I also don’t think I could ever put on the blue suit and sit in the office every day again. Third, I love giving back. This is the first time in my career that it’s not just about selling shoes. Having a positive impact on Indigenous communities is really meaningful, especially since this is likely my last tour of duty. It revs my engine each day giving back to what’s much bigger than a shoe company. I love what this new model represents as an authentic brand in the marketplace. At this point in my life, it’s a dream job.

SM: I love the ability to focus on my true passion, which is making a social impact. Having served as CEO, de facto COO, warehouse packer, etc. for nearly 25 years, it got quite tiring and challenging at times. With Greg taking on CEO duties, I’ve gotten a little bit of my life back and I feel super reenergized and focused. I’m more convinced than ever on meeting some of the lofty goals we’ve set on both the social impact and growth sides. I believe we’re going to get there, and I’m excited about all the good stuff that’s to come.