At 250, Birkenstock is older than the United States of America. The venerable Germany company also predates many of its home country’s most famous landmarks, including Neuschwanstein Castle, the Brandenburg Gate, and the Berlin Cathedral. And it has been in the design business longer than fabled heritage brands like Louis Vuitton, Dior, and Givenchy, with which it shares a connection through L Catterton, the private equity arm of luxury goods giant LVMH. These are all remarkable feats, especially when you consider that the average lifespan for a business is somewhere between 10 and 20 years, depending on the data you source.

During its long life, Birkenstock has been everything from a Haight-Ashbury hippie accoutrement to a Bushwick hipster essential. It has been the favorite shoe of brainy tech dudes (an old pair of Steve Jobs’s brown suede Birkenstock Arizona sandals sold not along ago for over $200,000) and the darling of haute couture, gracing the feet of Kate Moss, Heidi Klum, and—most recently—Margot Robbie in Barbie. Through it all, Birkenstock has stayed true to its mission—crafting comfortable, ergonomically designed, flat-bottomed footwear with care and high-quality natural materials.

“The 250-year milestone is a privilege and a special moment,” says CEO Oliver Reichert, now in his 15th year with the brand. “In a world where consumers spend their money more and more intentionally, it’s getting difficult for brands that have no real purpose. Birkenstock is a pure, purpose-driven brand. We’re not a footwear company; we’re a footbed company selling the experience of walking as nature intended. Our products serve a primal human need and offer a real functional benefit to consumers. We’re selling a purpose that never goes out of style.”

Another key to Birkenstock’s longevity is its passion for innovation, says Andrea Schneider-Braunberger, managing director of the Society for Business History, and official historian for the brand. “From the outset, the Birkenstock family focused on transforming their expertise as traditional shoemakers into pioneering advancements in foot health to improve their customers’ daily lives.”

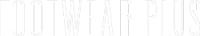

David Kahan, president Birkenstock Americas, calls “Birks” the ultimate symbol of democracy. “Birkenstock resonates with people of all walks of life,” he says. “It has universal appeal that transcends cultural and social boundaries. What other brand has such a diverse and loyal following that includes Michelle Obama and Tucker Carlson? Despite representing opposite ends of the spectrum, they share an appreciation for the comfort and quality. That widespread appeal is a testament to our commitment to creating products that prioritize quality and timeless design.”

When Kahan joined the company 12 years ago, he was still a self-proclaimed sneaker guy. “Birkenstock was the only non-athletic brand I had ever worn,” he says. But he recognized that if a dedicated few could love the brand so deeply, then millions more could too. “Our task was to unlock this potential and broaden our appeal without losing our core values and the essence of what makes Birkenstock special,” he says. “Over the years, we’ve done just that, transforming the brand from an outsider in the footwear industry to a global icon.”

How it all Began: a Crash Course

Of course, back in the 1700s, when cobbler Johannes Birkenstock was honing his craft in the small village of Langen-Bergheim, not far from Frankfurt, he would have been stunned to learn that he was laying the groundwork for what would become one of the world’s best-beloved and most enduring companies. The earliest recorded mention of Johannes is in the archives of his local church, listing him as a shoemaker in 1774. He taught his nephew, who shared his name, how to handcraft shoes, and so began the family tradition of passing the craft along to successive generations.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution swept through Germany, bringing with it factory-made goods and shrinking the demand for traditional crafts as well as the skilled tradespeople who made them. Fortunately, Johannes’ great grandson, Konrad Birkenstock, was not a man to be sidelined. A born inventor, he opened a workshop in Frankfurt and introduced a series of breakthroughs in footwear, including anatomically shaped lasts, shoes designed differently for right and left feet, rounded heels, and malleable soles that allowed the foot to roll. Later, he created an anatomically shaped insole, contoured for arch support. Eventually he combined the inner and outer pieces into what he called the Birkenstock Health Shoe. His design flew in the face of the then-widespread belief that the best way to ease foot pain was to wear shoes that kept your feet firmly in place. Konrad’s ingenious—and effective—Health Shoes were intentionally flexible, which helped wearers walk more naturally. He continued to experiment with design and material, and, in 1913, introduced flexible insoles that he called Footbeds, made partly from cork. He and his son Carl set off traveling through Europe to educate fellow shoemakers about the benefits of Birkenstock’s anatomically shaped lasts with flexible insoles.

Carl took a page from his father’s book and introduced more innovations. He opened his own company with his brothers and set up a series of podiatry courses he called the System Birkenstock in 1932, followed by a podiatry textbook in 1947.

Carl’s son Karl joined the family business in 1954 and created what he called the Original Birkenstock-Footbed Sandal, featuring the company’s trademark flexible cork-latex footbed and an adjustable strap. He debuted it at the 1963 shoe trade show in Düsseldorf, but the fashion world scoffed at the odd-looking product. Undeterred, Karl changed course, directing his outreach efforts to doctors, who could help promote the shoe’s health benefits. Before long, Birkenstock sandals had developed a loyal fanbase among healthcare workers.

Counterculture Baby

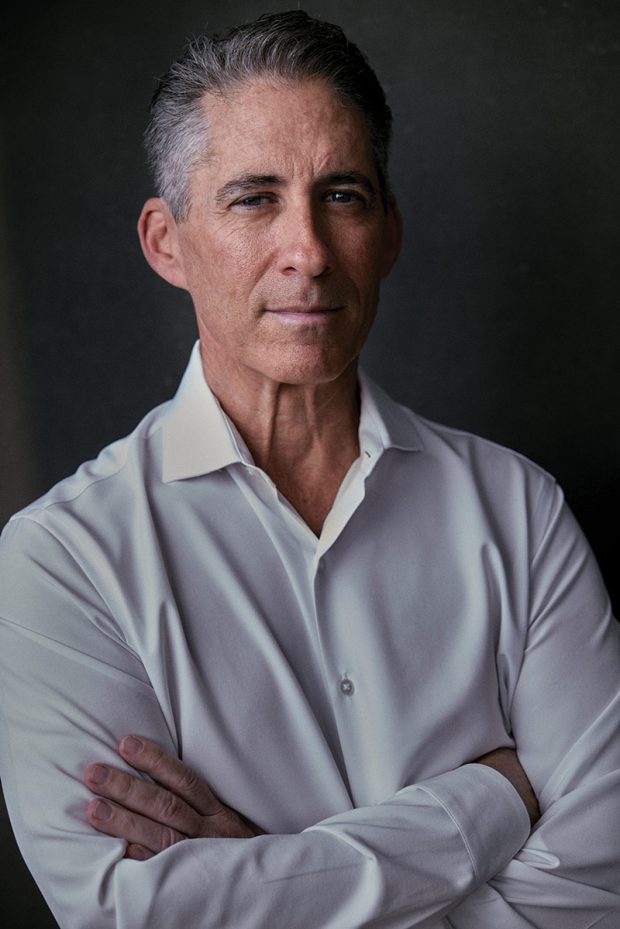

In the 1960s, an American tourist named Margot Fraser found her feet aching during a visit to Germany. She bought a pair of adjustable single-strap Birkenstock sandals (now known as the Madrid) and was so impressed that, after she got home to San Francisco, she bought the rights from Karl to import and sell them in the U.S. Unfortunately, shoe retailers reacted much like the Düsseldorf crowd had. When they refused to carry the strange-looking shoes, Fraser approached health food stores instead. Her timing couldn’t have been better. It was the height of the hippie movement, and countless flower children who came into the stores to stock up granola and wheat germ were suddenly besotted with Birkenstock sandals. Natural materials? Earthy colors? Unpretentious, comfortable styling? The shoes seemed tailor-made for free spirits. When Birkenstock introduced a new model with a second strap (the now famous Arizona) in 1973, the hippies dug them too.

Tip Top Shoes in New York was among the first to board the Birk bandwagon. “My father was of German heritage and he knew about Birkenstock, so we ordered the Zürich in taupe and the Arizona in sand in the Woodstock era,” says owner Danny Wasserman. “People came in and tried them on, and they started to sell. We started running a postage stamp–sized ad in the back of The New York Times with a photo of the Arizona, and more people came in to buy Birkenstocks. Retailers started to ask me what they were because 99 percent of them didn’t know. Next, we ran ads in The Village Voice and Rolling Stone. Soon we’d have six or seven people outside waiting for us to open so they could buy Birkenstocks. It was amazing. Then we did a trunk show with Margot Fraser and Karl Birkenstock, and we sold 100 pairs that day!

“They looked weird on everybody,” Wasserman says with a laugh. “We used to run ads that said, ‘the ugly shoe that makes you smile.’”

Seemingly overnight, Birkenstocks became a counterculture icon. To wear them was to make an anti-establishment sartorial statement. It was the first of many times fringe groups, underground movements, and rebels would be drawn to the brand and co-opt it as a political fashion statement.

Perhaps inevitably, as the flower power culture fell out of favor, Birkenstocks dropped off the pop culture radar, too. The medical profession, eco warriors, and older buyers in search of comfort were still enthusiastic (the closed-toe Zürich style was a particular favorite), but by the 1980s, the brand was finding it hard to shake off the Woodstock generation association. Preppies and punks dismissed them as “Jesus sandals.”

Then an extraordinary thing happened: The fashion world started to discover Birks. In 1985, British Elle featured them in a fashion shoot. Five years later, The Face magazine showcased Kate Moss (then 16) wearing Birkenstocks. Admittedly, not everyone embraced the idea. Perry Ellis famously fired Marc Jacobs after he put Tyra Banks in Birkenstocks on the runway as part of his groundbreaking spring 1993 grunge collection. Despite the critics—or perhaps because of them—the collection cemented Jacobs’ reputation as a visionary and kickstarted Birkenstock’s popularity with Seattle musicians, So Cal skaters, and college kids, who liked both the comfort factor and the anti-establishment vibe.

Fashion Meets Function

As the new millennium dawned, Birkenstock’s appeal broadened. Stars like Gwyneth Paltrow and Jude Law were spotted wearing the brand in 2002. The following year, the company partnered with supermodel Heidi Klum, inviting her to put her own spin on the Arizona, Madrid, and Amsterdam as part of a special Glamour Collection. Klum’s interpretation—blinged up with studs, rhinestones, and frayed and faded denim—was such a hit that it paved the way for many more collaborations (including several follow-ups with Klum). The most headline-making was arguably Céline’s Phoebe Philo in 2012, when she lined Arizonas with mink and put “Furkenstocks” on the runway. Additional collaborations have included CNCPTS, Jil Sander, Maison Valentino, Proenza Schouler, Rick Owens, and Stüssy. Adding to the brand’s star power: Celebrities like Kendall Jenner and Gigi Hadid have turned out in Birkenstocks recently.

“In the early years, our strongest demographic was women in their 50s with foot problems, but we don’t really have a demographic profile anymore,” according to Frank and Toni Budworth of Birkenstock Midtown in Sacramento, CA, now marking its 38th year of carrying the brand.

“Right now Birkenstocks appeal to everybody,” agrees Wasserman of Tip Top, which carries approximately 50 styles of Birkenstock these days in colors from turquoise to burgundy. “The Boston in taupe suede was the hottest shoe on the market both this year and last year.” Wasserman links the brand’s current fashionability to the fact that, “since Covid, everyone is looking for comfort, and the brand is famous for it.”

Kahan believes Birkenstock will always transcend trendiness. Once people get hooked on the comfort of the footbed, “they become lifelong fans,” he says. “They don’t see us as a flavor of the moment.”

He should know. Kahan himself was an unlikely convert long before joining the company. “After suffering a running injury and being diagnosed with plantar fasciitis, my podiatrist recommended Birkenstock for recovery. I was skeptical. Coming from Brooklyn, I saw it as a brand associated with freaks, hippies, and outcasts, far removed from my personal style,” he says. His perception changed dramatically when he experienced the transformative support of the Birkenstock footbed. “After wearing them at home for a few weeks, my injury improved almost magically. I became a missionary for the brand, wearing my Arizonas everywhere.”

Troy Dempsey, owner of The Heel Shoe Fitters in Green Bay, WI, sees proof of the Arizona’s lasting popularity every day. “Our back room is a sea of blue boxes that say Arizona on them,” says Dempsey of the shop, which has carried Birkenstocks since the ’70s. He estimates that the store has sold more than 250,000 pair over the years, culminating in a recent 250th Anniversary Celebration of Birkenstock at The Heel. “We sold almost 400 pairs at full price. It was our most successful event to date,” he says.

Eyes on the Horizon

Of course, incredible success stories like Birkenstock’s are never quite as simple as sticking to a winning formula. They demand brilliant foresight and careful stewardship. Reichert was brought aboard as chief advisor in 2009, along with Markus Bensberg (who has since stepped down), in the hopes that they would bring the external perspective and management savvy needed to lead general change. One of Reichert’s first insights when the family handed him the reins was that “Birkenstock was a sleeping giant with all the essential ingredients of a super brand—a rich heritage, an unyielding approach to craftsmanship combined with an obsession for quality, a vast product archive with an impressive variety of iconic silhouettes, a steadily growing global following sharing similar values and beliefs, and a uniquely democratic approach to innovation, pricing, and distribution,” he says.

Reichert has made it his mission to turn the sleeping giant the global super brand he knew it could be. “From the first day, we turned over every stone and pushed every button to release the energy and create momentum for the brand. In some areas, it was quite tough to reach our goals, but we’ve done a lot right in the last 10 years,” he says.

One smart move was selling a majority stake to L Catterton in April 2021. The brand continues to operate its business independently, but now has access to L Catterton’s global network and resources. Another was last year’s IPO, which put the company in the hands of a broad, international audience and “gave our global fan base the opportunity to invest in their favorite brand,” Reichert says.

Though Birkenstock now boasts distribution to over 100 countries and offers approximately 800 styles, manufacturing is still based in Germany. At press time, construction was underway on a new production facility in Pasewalk.

“We engineer and produce 100 percent of our footwear in the European Union, one of the safest and most regulated markets in the world,” says Reichert. “Germany has been the heart of our operations, and expanding production here allows us to uphold the high-quality standards that define our brand. Our workforce possesses the expertise and craftsmanship to produce footwear that meets our rigorous standards. By expanding locally, we maintain greater control over our production processes, ensuring that each product embodies the quality that Birkenstock is known for.”

These days, the company is balancing veneration for its rich 250-year history with intense focus on the chapters ahead.

“It is much more important for us to look ahead and ignite the future,” says Reichert. “The risk of a cultural heritage is that you suddenly find yourself as the keeper of your own museum surrounded by old masters that nobody wants to see anymore. I will not allow that to happen. If you want to remain relevant as a brand today, you have to allow for creative and meaningful new interpretations through the lens of the next generation of consumers.” And that is exactly what Birkenstock is doing.

With sound leadership and continued innovation that doesn’t sacrifice authenticity, Schneider-Braunberger firmly believes Birkenstock “has the potential to thrive for another 250 years.”

Not bad for what began with a humble cobbler’s shop and innovated products that were once derided as “tree stumps” but went on to win hearts world over, becoming a multi-billion-dollar brand and a legend for those famous, fabulous “ugly shoes that make you smile.”