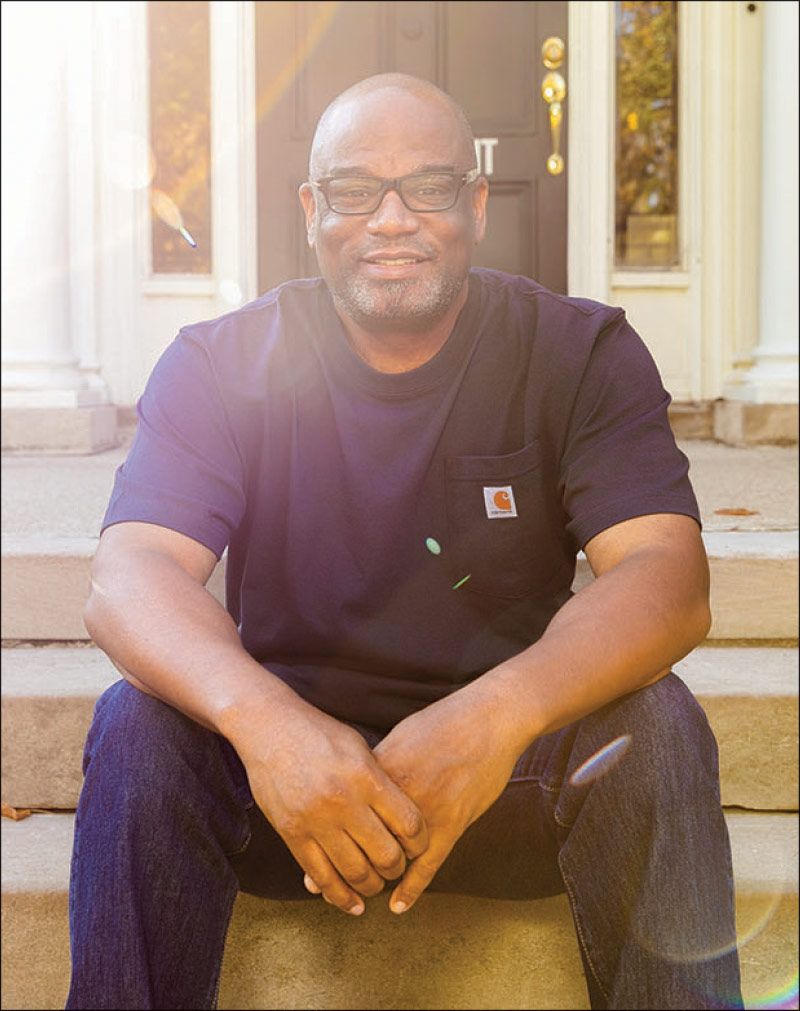

Dr. D’Wayne Edwards is a statistical anomaly of Powerball proportions. For starters, the odds of surviving past his 18th birthday in what was then the murder capital of America—Inglewood, CA in the ’80s —were against him. His odds of living to see 25 decreased—while the odds of winding up in jail increased—with each passing year. The odds of attending college (he didn’t), let alone becoming a president of one (he is) were astronomically low. The odds that Edwards would become one of three sneaker designers in history to have at least one of their designs on sale at Foot Locker for 30 years running were longer than getting struck by lightning on a sunny day. Edwards, a McDonald’s employee during his teen years, probably had better odds of winning its Monopoly game (reportedly one in 451,822,158) than of achieving all that he has accomplished in his remarkable career.

Edwards’ career story reads like a Hollywood script. Poor kid lives out his childhood dreams to become head sneaker designer for the pinnacle of athletic brands (Jordan) through determination, talent, passion and a dash of sneaker fate—thanks to LA Gear and Skechers Founder Robert Greenberg, who gives him his big break. (More on that later.) Hip hop legends Biggie Smalls, Tupac Shakur and Snoop Dogg wear his creations, as do sports heroes Derek Jeter, Carmelo Anthony and Roy Jones, Jr. Edwards even designs the equestrian boot worn during a U.S. gold medal performance at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

But that’s just part one of this epic, sneaker-laced biography. The second half of Edwards’ career is a pay it back/pay it forward story sure to keep audiences riveted. Once again, it defies all odds as it sets in motion a transformation of the entire footwear and design industries. In this heroic true tale, Edwards walks away from his 10-year reign as Design Director of Jordan Brand to launch an academy aimed at teaching the art of sneaker design to people of color—for free. His Pensole Design Academy quickly gains the support of leading sneaker companies like Adidas, New Balance and Nike, which fund bootcamp-like, two-week design programs as a way to bring long-overdue diversity to their workforces. Soon after, art schools reach out to partner with Pensole. Edwards, who couldn’t afford to attend college, soon finds himself leading classes at the top product design school in the country (ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, CA), the number-one fashion institution (New York’s Parsons School of Design), and one of the world’s top engineering schools (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Along the way, a steady stream of Pensole graduates begin creating their own sneaker designer legacies.

How’s that for a Hollywood ending?

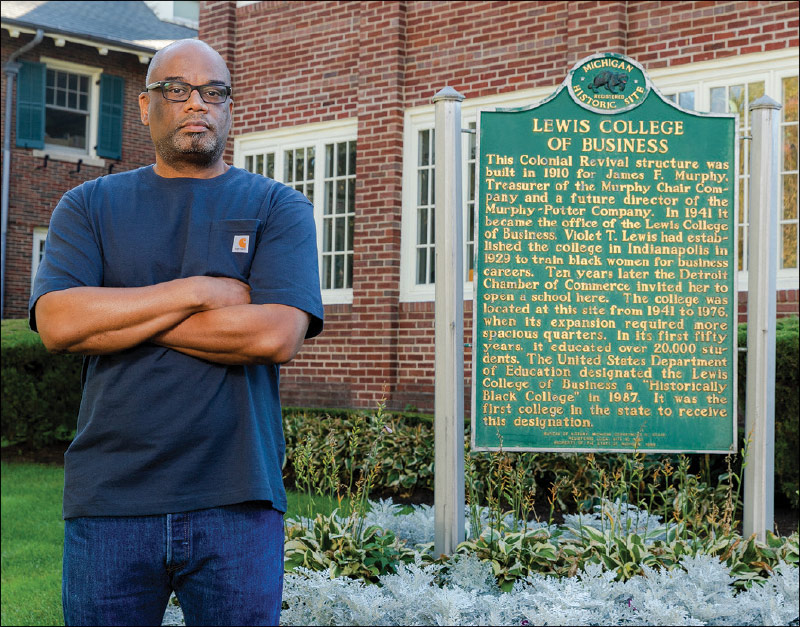

But Edwards’ incredible career story is still unfolding. The latest chapter will have far-reaching and lasting impacts in the worlds of footwear, apparel, packaging and furniture design. That’s because Edwards’ Portland, OR-based Pensole Design Academy decided to go to college. Last fall, Edwards, along with co-founding partners the Gilbert Family Foundation and Target, petitioned Michigan to become the newly formed Pensole Lewis College of Business & Design (PLC) in partnership with the College for Creative Studies (CCS). In doing so, the Detroit-based institution has reopened the state’s sole HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) with a new name and vision. The school, the first HBCU to focus on design, will offer free tuition to a majority of students, supporting people of color who are creatives, designers, engineers and business leaders. The school is also the first mothballed HBCU in the country to officially reopen. Plans include building a new campus and expanding degree programs.

There’s more. Last month, DBI, parent company of DSW, announced it is partnering with PLC on the opening of JEMS by Pensole, the first Black-owned U.S. footwear factory. The $2 million investment will produce shoes designed by PLC graduates and will be sold exclusively at DSW.

All this because a poor kid in Inglewood absolutely loved sneakers. That’s where Edwards’ story begins—one truly made for Hollywood.

Scene 1: The Original Sneakerhead

All Edwards ever dreamed about as a kid was to become a sneaker designer. He started sketching kicks in middle school and, by high school, he was stopping into local hardware and shoe repair shops regularly to pick up the early tools of his trade to customize his sneakers—an exacto knife, duct tape and dye. Soon he was customizing kicks for his basketball teammates and other kids at school. “That became my little side hustle, but it really started because I had to be different than everybody else,” he says. “I still have the same problem to this day: My fear is walking into a room and someone has the same pair of shoes on as I do.”

At age 17, Edwards even won a sneaker design competition sponsored by Reebok—only to be told to come back in four years after he earned a design degree. (It was a slight Edwards vowed he would—and did—avenge.) But college was out of reach financially. Worse, Edwards’ high school guidance counselor tried to shoot down his dreams before they even got off the ground, telling him: “No Black kid from Inglewood is ever going to become a footwear designer.” Edwards refused to listen.

“I actually saw her six years into my career, in front of Skechers offices in Manhattan Beach,” he recalls. “She asked what I was doing and I said, ‘What you told me I wasn’t going to do.’” Edwards, though, understood what she meant by her statement. “She was trying to tell me to just get out of the city alive,” he says. “She felt that if I could get into the military, I could be safe, or if I could find a more realistic job, I wouldn’t get caught up in the streets and end up where some of my friends did, which was in the ground or in jail.” He considers her advice a blessing. “I needed that extra motivation to prove her wrong.”

Edwards’ high school actually played a huge role in living out his sneaker designer dreams. During freshman year he was kicked out of art class—he wanted to draw sneakers, not fruit—and, as “punishment,” put into a drafting class. That led to an off-campus program, beginning his junior year, that taught interior design. Edwards took an hour-long bus ride to attend the class, which is where he was exposed to another world. “Once I got introduced to design, I started designing shoes instead of just drawing someone else’s.” The last sneaker Edwards drew in high school was his version of what he thought the Air Jordan 2 should look like, which came out in ’88, the year he graduated from high school. Little did Edwards know then that, in a little over 10 years, he would become Design Director of Jordan Brand.

Scene 2: Game On!

Fate plays a leading role in Edwards’ story. His big break comes by chance after landing a job at a temp agency. Edwards’ coworker didn’t want to file papers at LA Gear, so they sent Edwards instead. “If he’d gone, my whole life would have been completely different,” he says.

Edwards was thrilled just to be inside a sneaker company. He peppered the designers with questions, asking how he might get a job like theirs. They all told him he needed a college degree. Then Edwards took matters into his own hands, through LA Gear’s suggestion boxes. Ever the entrepreneur, he put sneaker sketches drawn on 3×5 index cards in the box every morning before he went to work in the mailroom for sixth months—180 shoes! “That was my Instagram,” Edwards says. “I knew somebody would see it, and I hoped at some point they’d show it to the design department and they’d buy it from me.”

Then one day Edwards heard his name over the intercom, with an order to report to the president’s office. “I’m like, damn, did I mess up that bad at filing papers that Robert Greenberg wants to fire me personally?” He walked in slowly and saw a bunch of his design cards splayed out on Greenberg’s desk. He braced for the CEO to lower the boom. Instead Greenberg said, “So, I hear you’re the person putting all these sketches in my boxes.” Edwards apologized profusely and said he just loved drawing sneakers. After a few get-to-know-you questions, Greenberg asked, “If I offered you a job, would you accept it?” Edwards’ answer was an unequivocal yes!

“Robert offered me my first professional footwear design job right after my 19th birthday,” he says.

Greenberg, who has decades of experience building and leading multi-billion athletic footwear companies, knows talent when he sees it. He also spotted two qualities in Edwards that warranted giving the kid his big break: “Ambition and passion,” Greenberg says. “D’Wayne just wanted so badly to be a designer.”

Edwards is eternally grateful to Greenberg, whom he considers his first mentor. “I learned my whole existence as a business person from just watching him,” he says, recalling how he tried to beat Greenberg into work. “It took me four tries–and it was 5 a.m.—in order to beat him there!” Edwards became a student of Greenberg’s work style. “Robert had a routine of consuming knowledge before the day started and setting a to do list by speaking into this handheld recorder,” Edwards recalls. “For 33 years since, I’ve written a do list every day and read to get some knowledge. I’ve added meditation into the process, but everything I learned from Robert back in the early ’90s I still do today.”

Greenberg’s instincts were spot-on. Edwards hit the ground running at LA Gear. And when Greenberg left to launch Skechers, Edwards soon followed—but not before a year-long stint designing shoes for the Black-owned MVP Products in Detroit. “It was the first time I ever saw snow! I was 24 years old!” recalls Edwards of the learning experience. “I met some great designer friends, and I’d watch Eminem and D12 perform at my friends’ stores on Saturday nights before they became famous.”

Edwards kept in contact with Greenberg and told him about a growing streetwear apparel movement happening in L.A. with brands like Cross Colors and Karl Kanai. The brands were going to be big, he told his friend/mentor, and if they ever decided to do shoes, Skechers should think about getting in on the trend. Greenberg listened and, after signing the licensing deals for both brands, he recruited Edwards as head designer. Soon after, Edwards’ designs donned the feet of hip hop royalty—Tupac, Biggy, Snoop, Dr. Dre and Nas. “Those were not paid endorsements,” he says with pride. “It was just crazy to think these legends of hip hop were wearing my shoes.”

Edwards had officially arrived. Over the next few years, he designed for Cross Colors and Karl Kanai and, when those license deals were not renewed, Greenberg gave him the green light to launch his own brand, Sity. “I was traveling all over the world and noticed how sneakers were different in other countries, and I wanted to bring back some of that style to the kids in the ’hood,” he says. Sity’s first collection sold out, and in 2000 an industry publication ranked the brand second to watch out for behind Jordan. Pretty good company—and another sign of things to come.

Sity plans were moving forward, but then Skechers began transitioning to going public. The decision to divest of new projects became paramount, and Sity was one of the casualties. “Leaving Skechers was hard,” Edwards says. It was hard for Greenberg too, but he knew he had made a positive impact on Edwards’ life. “Nothing feels better than respect,” he says. “My passion is discovering talent in people and helping them grow and prosper.”

Scene 3: Atop the Sneaker Mountain

Edwards, fresh off of Sity, needed a new job. That’s when a colleague tipped him off that Nike was looking for someone to help them compete with Timberland in the outdoor space. The friend connected Edwards with Drew Greer, an “industry legend” who Edwards says prepped him for the interview. Edwards will never forget that first day at the Beaverton headquarters. “It’s every sneakerhead’s Wally World,” he says. “I was in awe; I’d never even been to Oregon.” Two weeks later, Nike ACG offered him a job. As far as he was concerned, it was a daily pass to the world’s greatest sneaker park.

Nike ACG was located in the Jerry Rice building, one floor below Jordan Brand. “I was this close to Jordan, so I’d sneak upstairs just to smell what the air was like,” Edwards confesses. Design director Bob Mervar didn’t mind. One day Mervar asked Edwards if he would like to “work on some stuff.” Edwards jumped at the chance for another side hustle. Within a year, a full-time spot opened and Edwards got the job. The following year, Mervar left for another category and Edwards assumed the role of design director. He had to pinch himself—often.

“The most memorable aspect of the experience, besides meeting Michael Jordan, was my second project, which was a redesign of the Air Jordan 2,” Edwards remembers. “That was the last shoe I drew in high school. So 12 years later that was a full-circle moment that told me this is where I was meant to be.”

Edwards held court over Jordan Brand designs for the next decade. At the beginning, it was a $275 million business; 10 years later, it had zoomed to $1.3 billion. “It was an amazing ride,” he says. “We worked extremely hard. But everybody there just loved the brand so much that we didn’t know we were killing ourselves.”

Some memorable designs of Edwards’ Jordan Brand era include gold medal-winning shoes designed for Carmelo Anthony, University of North Carolina’s two NCAA championship teams, NBA star Ray Allen and Roy Jones Jr., who won several belts in Edwards’-designed shoes, including the heavyweight championship in 2003. “He actually signed a half pair for me on the day before as the ‘new heavyweight champion,’” Edwards says. “That was pretty cool.”

Edwards says his designs are all his children; there are no favorites. “I’ve always had the mindset that if I picked a favorite, whatever I did next wouldn’t be good enough.” He enjoyed pushing the envelope each season. He loved his Nike tenure, but the work was grueling and, toward the end of his decade, he wanted to give back to young designers like himself—kids who needed their big break. He didn’t want to be known only for his designs. When first visiting Nike, “I was introduced to people by their name and the shoe they designed,” he recalls. “I understood the reference, but I didn’t like it.”

Around this time, the sneaker game went digital with forums like Nike Talk, Nice Kicks and ConceptsKicks. Kids often posted their sketches. A few even emailed them directly to Edwards. “These kids were hungry to design sneakers for a living,” he says. “They would love to do what I’m doing, so I never took my job for granted.” One such-up-and-comer was Jason Petrie, whom Edwards communicated with online; Petrie went on to design all the Lebron James styles for 10 years. He later thanked Edwards for the free mentoring. That’s when Edwards started devoting more attention to mentoring his interns—and that made him rethink his industry legacy.

“Even though Spike says ‘It’s gotta be the shoes,’ I didn’t want it to be that,” he says with a laugh. “Mentoring drove me to think about things differently.”

In 2008, Edwards created the Nike design competition Future Sole. At the time, the company employed only six Black footwear designers. Nike wanted to address its diversity problem. But how? Edwards came up with the idea of a competition to level the playing field for candidates who didn’t necessarily have a degree. Since he was designing shoes for Carmelo Anthony at the time, he asked him to be the face of the program. He also asked Lisa Leslie, a fellow native of Inglewood, to be the face for women hopefuls.

“I wanted the kids to see famous athletes who love sneakers, just like they do, encouraging them to be designers,” he says. The first year 800 kids entered the contest. The next year it was 10,000, followed by 250,000 and close to 900,000 in the fourth year. The 12 winners from those competitions are all professional designers today. The program worked. “It also showed that this is real—a lot of kids want to be sneaker designers, but they had no path,” Edwards says. “This gave me a glimpse into what could be possible.”

Scene 4: An Educator is Born

Coming off the success of Future Sole, Edwards took an eight-week sabbatical. He thought about the kids he had mentored who had gone on to become successful designers. Realizing he drew the greatest professional satisfaction from their achievements, he decided on a career change.

“I wanted to give it all back, because those kids are just like me when I was a 17-year-old in Inglewood trying to figure out life. That’s what I want to be remembered by,” Edwards says, noting that The Rules of the Red Rubber Ball, written by a former Nike exec, helped crystalize his desire. “It’s about finding your true passion, and I realized my red rubber ball is a yellow No. 2 pencil, because it designed my life. Without that object—one that I use to this day—I wouldn’t have done anything that I’ve done for the last 33 years. That’s why the school is named ‘Pensole.”’

Launching a school from scratch is not easy. But Edwards had the bones of a curriculum from the mentoring he’d been doing. So he reached out to the University of Oregon at Portland, which had just launched a product design program, and asked to teach a class. They agreed and the Pensole Design Academy was born.

“I flew in 40 students from around the world,” Edwards says of his inaugural class. “I designed a two-week program, because that was how long you had to design a shoe from start to finish at Nike. I wanted to put the kids through exactly what it was going to take for them to make it in this industry.”

The students logged 14-plus hours every day and loved every minute of it. Edwards also brought in Nike designers as guest mentors. “They got an immersive experience, as it was important for them to see that there were multiple ways to get into this industry,” he says. Proof of Pensole’s potential: Of the 40 kids in that class, 37 work as designers in the industry.

Word quickly spread. Edwards received a call from the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena—the school that would later award Edwards an honorary degree—asking him to teach a class. It marked the start of a 10-year partnership with the institution. Soon after, Parsons School of Design reached out to Edwards. So did MIT. “So here I am, the kid who never went to college, teaching at the top design schools in the country,” Edwards says. By that point he knew he didn’t want to return to corporate life. “I fell back in love with design and teaching. Seeing that look in the kids’ eyes…I didn’t want to remove that emotion by going back to work.”

Edwards officially left Nike on April Fool’s Day 2011. Over the next decade, as he grew Pensole Design Academy, he gathered knowledge on what would become PSL. He didn’t know with who, when or where yet, but teaching at top designs schools laid the foundation. “I was learning about culture, curriculum and the education system,” he says. “I took bits and pieces from them all.” It’s the same way Edwards approached design projects. “I learned everything I could and then, to use a Bruce Lee expression, took what was useful and released what was useless.”

Edwards attributes Pensole’s success to its strong ROI. “Job placement was my ROI,” he explains. It was a win for all parties. “The brands made the investment in the students that they couldn’t find in traditional ways, and we taught them exactly the way they would work, so our kids didn’t need as much break-in time as those graduating from traditional schools.”

One such satisfied graduate is Aric Armon, footwear designer for U.S. Football at Adidas. The word that first comes to his mind when thinking of Edwards is mentorship. “The lessons I learned from him have influenced my life in profound ways, both professionally and personally,” Armon says. “He told us right from the beginning that it was our duty to take what we learned and pass it along. In that way, D’Wayne is a mentor to mentors, and his impact continues to exponentially grow with every new generation of talent.”

Jordan Johnson, associate product manager and designer for New Balance, says Pensole is the reason he is where he is today. “The ample networking opportunities combined with the wealth of knowledge provided by D’Wayne and the Pensole staff are priceless,” he says. “It is truly an experience that cannot be replicated anywhere else.” Johnson learned everything there is to know about the process of creating a product the “D’Wayne Way.” Those tenets include: Always design for a purpose, as “The world doesn’t need more shoes”; solve problems; create product for specific consumers; and integrate true storytelling into the product. “This formula always creates the best product,” Johnson says.

Scene 5: College Bound

The PLC deal came together quickly, starting in mid 2020. Pensole had been growing steadily—Edwards was looking for a bigger campus site in Portland—but the murder of George Floyd changed everything. Corporations started reassessing their investment in Black communities, and Edwards decided to pivot.

“Pledges started happening, and we’re talking billions of dollars,” he says. But when it came to potentially donating to design schools, corporations discovered few options. Of the 96 schools in the U.S. that offer design or art programs, Black students comprise only nine percent of total enrollment. Worse, only two percent of them graduate. Just nine percent of HBCUs offer design programs, and those are in graphics and apparel—none offer product design, which is the primary degree for athletic footwear. “That’s why there’s a lack of diversity in the industry—because those kids aren’t in college,” Edwards says.

Corporations began reaching out to Edwards. They liked Pensole’s model because it got results. Its success had already caught the attention of a Dan Gilbert, founder of Quicken Loans and Rocket Mortgage, who suggested on several occasion that Pensole move to Detroit. “I kept saying no. It didn’t make sense, there was no shoe industry in Detroit,” Edwards recalls. But then fate dealt him another winning hand.

In mid 2020, Edwards was speaking with a former student about how Detroit’s CCS should partner with an HBCU to increase its diversity. The former student mentioned that Detroit used to have an HBCU, the Lewis College of Business. Edwards was immediately intrigued. He researched the founder (Violet T. Lewis), the reasons the school closed and why its efforts to reopen failed. A realtor who had just sold the school’s building put Edwards in touch with the Lewis family. He contacted them and shared his vision for reopening the college with a design program component. “They loved the idea. They said their grandmother would have loved what we teach at Pensole, because that’s how she started the school in 1928 in Indiana,” he says. “They liked the vision I had for the college moving forward, so we entered into an agreement to bring it back.”

Edwards now had a good reason to call Gilbert, who committed funding as a founding partner and offered to match anyone who matched his initial donation. Edwards also got support from Target. He was meeting with the company about improving diversity in their product cycle and mentioned his plans to reopen an HBCU in Detroit. The retailer offered to contribute funds, and is now a founding partner. “They immediately understood the importance of what this could mean for our industry,” Edwards says. That support led to the partnership with CCS, an established design school that offers larger infrastructure and guidance.

Still there have been hurdles. For starters, the HBCU had been closed for eight years, so it needed to be accredited. That required creating a bill, because there were no laws in Michigan that allowed a college that had closed to reopen. Also, the state had never officially recognized Lewis College of Business as an HBCU. That meant another bill. “In two months, we wrote and got two legislative bills passed,” Edwards says. “That’s lightning-quick.”

Edwards attributes the expediency in making PLC a reality to its importance to Michigan and the design industries. Seeing it all come together is a dream come true, he says. “We’re officially recognized as an HBCU. The Gilbert Family Foundation and Target have blessed us with a huge jump start to get to this point along with CCS. Without them, none of this would be happening.”

Scene 6: Bright Future

PLC’s first class is this May, sponsored by Carhartt, a Detroit brand. Additional five-week classes on the docket this year are sponsored by New Balance, Versace, Jimmy Choo, Adidas, J. Crew, Proctor & Gamble and a Nike program with Serena Williams. “We’ll create a semester program starting this fall, where kids who live nearby can take classes one day a week,” Edwards says. “In the fall of ’23, we’ll start working toward our own degree program and begin to add majors like furniture and automotive design, packaging and graphics.”

PLC will initially be housed in the CCS building. Foot Locker is funding the footwear samples room. Hanes is building the apparel samples room. Herman Miller is providing furniture for the main studio. “We have amazing partners that believe in the vision of what PLC will be for our industry,” Edwards says, adding that students will stay in the St. Regis Hotel until dormitories are built on a new campus.

The fact that PLC has gotten this far, this fast defies the odds. Never in Edwards’ wildest dreams, as a poor kid in Inglewood, did he foresee this wonderful life unfolding. “That’s why I’m so grateful every day,” he says. “I feel like I’m winning every day, because I’m not supposed to be here.”

NPD industry analyst Matt Powell, says the reason Edwards is here starts with his tremendous design talent. “There are few sneaker designers who have shoes available for as long as Dr. Edwards has; his legacy speaks for itself,” he says, noting that his efforts to help people of color adds to that legacy. “This latest venture will solidify his work.”

PLC is just the latest chapter in Edwards’ odds-defying career. He’s creating an incredible industry legacy, and there’s much more to come. Not bad for the former mailroom guy at LA Gear. “Seeing what Mr. D’Wayne has accomplished, inspiring would be a harsh understatement,” his former student Johnson says. “D’Wayne is a revolutionary icon living in today’s time. My hope is that people recognize the great, selfless work he is doing to elevate aspirational creatives—more importantly, aspirational creatives of color. I am extremely blessed and proud to call myself a protégé of one of the greatest men of our time.”

High praise, indeed. Then again, it’s not every day someone changes an entire industry in a way that benefits everyone involved. “When I left Jordan I wrote down three things,” Edwards says. “One, make people forget I ever designed shoes, because if do, then I did something really good on the other side. Two, design the school that I wish I’d been able to attend and I’d hire from. Three, leave this industry way better than when I entered it.

“That’s been my journey the whole time,” Edwards says, noting he has only one regret. “I would love to sit down again with my two brothers, Michael and Ronnie, because they were the ones who taught me how to draw. I’m having the career that they didn’t have a chance to have.” Edwards adds, “It’s been an unexpected life that I’ve been blessed to have. And I’m not done yet.” •