“Generations come and go, but it makes no difference. The sun rises and sets and hurries around to rise again. The wind blows south and north, here and there, twisting back and forth, getting nowhere. The rivers run into the sea but the sea is never full, and the water returns again to the rivers, and flows again to the sea. Everything is unutterably weary and tiresome. No matter how much we see, we are never satisfied; no matter how much we hear, we are not content. So I saw that there is nothing better for men than that they should be happy in their work, for that is what they are here for, and no one can bring them back to life to enjoy what will be in the future, so let them enjoy it now.” —Ecclesiastes

“Generations come and go, but it makes no difference. The sun rises and sets and hurries around to rise again. The wind blows south and north, here and there, twisting back and forth, getting nowhere. The rivers run into the sea but the sea is never full, and the water returns again to the rivers, and flows again to the sea. Everything is unutterably weary and tiresome. No matter how much we see, we are never satisfied; no matter how much we hear, we are not content. So I saw that there is nothing better for men than that they should be happy in their work, for that is what they are here for, and no one can bring them back to life to enjoy what will be in the future, so let them enjoy it now.” —Ecclesiastes

One thing that has always struck me about this business is how people stick around long after they could have sailed off into the sunset with nest eggs the size of zeppelins. Take Nike founder Phil Knight, for example. He could have cashed out years ago. He certainly didn’t need more money, nor did he need the endless aggravation and stress that comes with running the world’s largest shoe company—a fact he discussed in detail in his captivating memoir, Shoe Dog. Knight, a former cross-country runner, soldiered on as the day-to-day point man for decades mainly because he genuinely loved what he did more than he loathed any hassles that came with the job. Above all, Knight loved the competition, the athletes he worked alongside, the product and, perhaps most of all, the thousands of employees who became part of his extended family along the way.

The same can be said of nearly every footwear executive I have profiled over the past 20 years. While most have far from Knight-like wealth, many are financially secure enough to have packed it in long ago. But they rarely do. No amount of money seems to quell their desire for the thrill of the chase, the battle for shelf supremacy and the obsession with keeping score of daily sale stats. Many claim the work keeps them young and living a life of purpose. In fact, those who try checking out often come back. There were only so many rounds of golf to play and beaches to visit before they missed their previous lives. As one returnee told me, “The phones stopped ringing.” The silence was deafening. He needed to be needed again. Another said he returned because retirement was turning his “brain to mush.” Say what you want about this business, but the speed at which it changes provides a constant workout for the mind.

Pat Hogan, president of newly launched Kizik and F.A.S.T. (Foot Activated Shoe Technology), is one such recent returnee. In Hogan’s case, the offer was too good to pass up. He believes the breakthrough construction (Handsfree & Hip, p. 12) has the potential to revolutionize the industry. In this business, you’re one great shoe (think Ugg Classic, Crocs Cayman, Merrell Jungle Moc) from $100 million and beyond. And once-in-a-lifetime opportunities like that are hard to pass up. In addition to riches, the potential to earn a place in footwear industry lore keeps many executives chasing the dream.

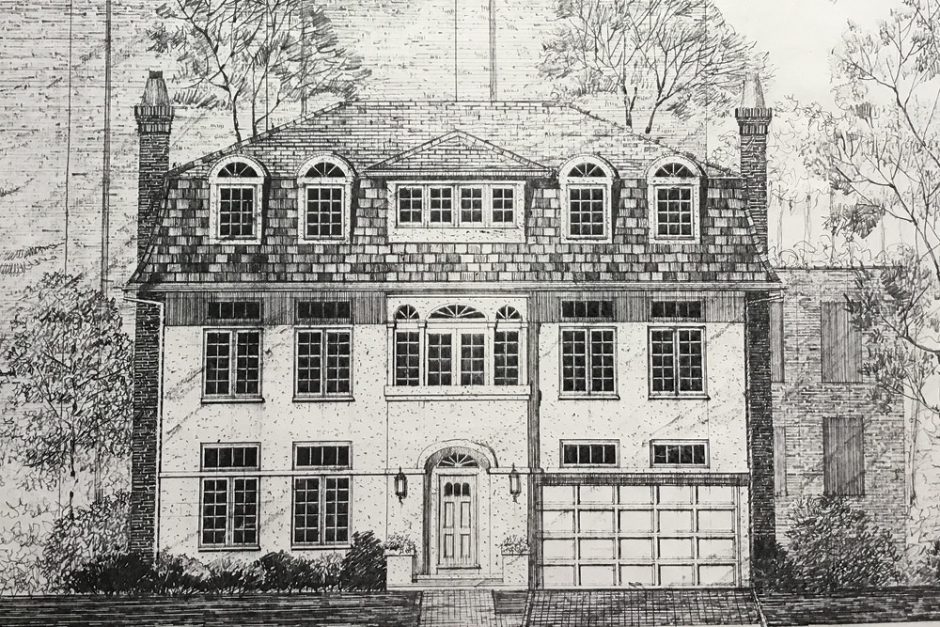

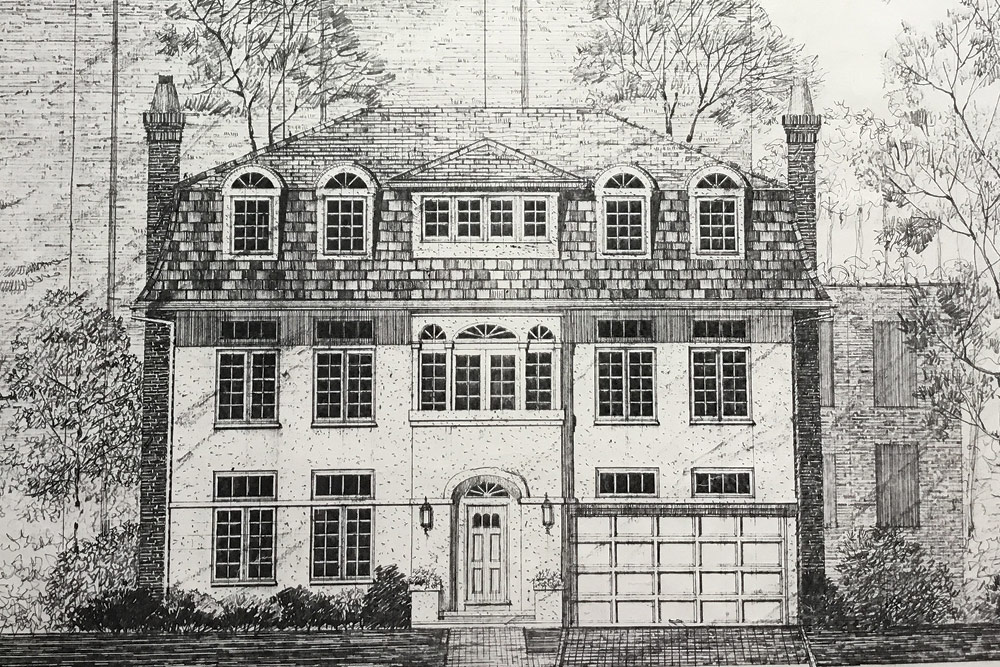

My father, who was an architect, didn’t need the money anymore, either. Yet he worked seven days a week into his 80s because he genuinely loved what he did for a living. He would sit at his drafting table in his home office for hours, dreaming up homes, restaurants and office buildings—whistling while he worked (literally) to big band greats of the ’30s and ’40s and, in season, following Baltimore Orioles broadcasts. As a kid, I often drifted off to sleep to the static-interrupted play-by-plays of those games.

Which brings me back to Ecclesiastes. While I would like to tell my mother I came across this bit of wisdom during CCD class, the truth is I first read it on a cover of John Mellencamap’s album The Lonesome Jubilee in 1987. (Sorry, Mom, but I got most of my religion from rock prophets like Bruce, Bono and John.) I was heading into my junior year of college and the “what am I going to do after I graduate” fears were mounting. This little passage helped put them into perspective: Find something you are (at least) decent at, that you enjoy doing and stick with it. It will give you direction and purpose in life. The idea has stayed with me ever since. It also fit my father to a T. Or should I say, T-square?

Despite being the son of an architect, I can’t draw a straight line. But I was always impressed with the extras my father included in his plans. He would spend hours adding exquisite details like leaves and shading that brought his designs to life. He was an artist, and each of his designs told a visual story. That’s a thought process I can still relate to: Each story has to be structurally sound and also pretty to read. There are plenty of nondescript houses, but there are also Fallingwaters. (My father was a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright.) The same goes for the written word. I’d like to think that’s the gift he passed on to me. R.I.P.