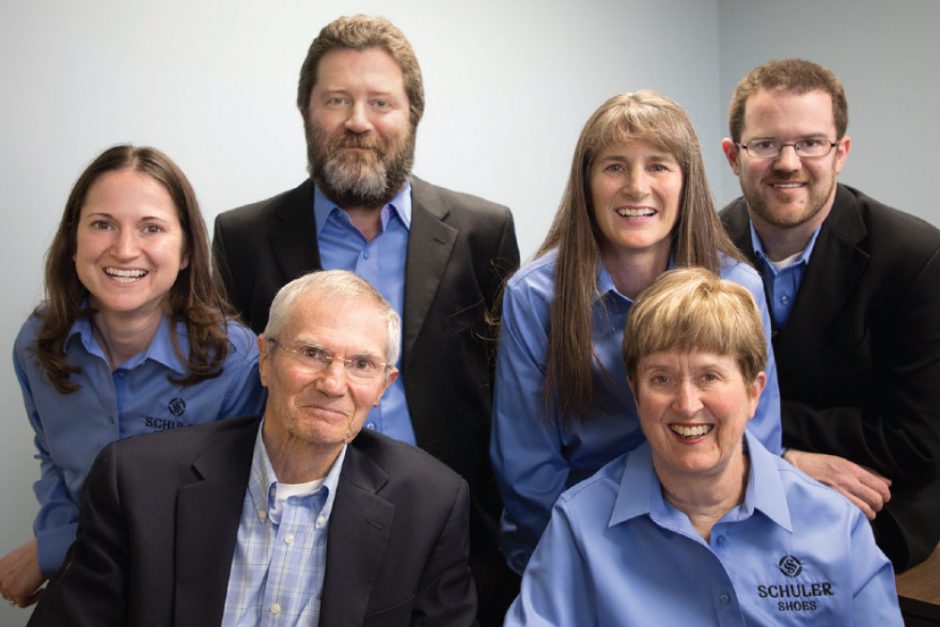

When John Schuler was diagnosed with cancer in 2005, it came as a stark wakeup call not only about his own future but about the future of his family business. If failing health forced him to relinquish control of his nine Minnesota stores, who would fill his shoes? Schuler Shoes had been handed down through successive generations of John’s family—starting with his great uncle, Vincent Schuler, who founded the family’s first store back in 1889 in Minneapolis—so passing it on seemed the logical choice. After all, John himself had bought the company from his father, Emmett, in the 1970s.

The problem was, John had four adult children. All of them worked full time for Schuler Shoes, which John had grown considerably in his three decades at the helm. Three of his children’s spouses were employees, too. Each child had unique strengths and an interest in the company’s future. Choosing one of them as his successor would be akin to picking a favorite from his sons and daughters—and announcing it to the public. It was not an enviable position.

Flash forward to 2018 and John, who recovered from cancer but has since faced other health crises, is still in the process of transitioning Schuler Shoes for the future, with input from his children, his wife and his children’s spouses.

Such a lengthy timeline is not unusual, according to experts. When it comes to a family business, generational transfers can be both a labyrinth and a landmine, fraught with emotionally charged conversations and tricky family dynamics like sibling rivalry—not to mention complex issues like trusts and estate planning. But, challenges notwithstanding, more and more retailers are making succession a family affair.

“In the past, when retailers decided to retire, they sold their businesses,” explains Chuck Schuyler, president of the National Shoe Retailers Association. “But in today’s environment, that’s a difficult thing to do. Many of our members have family in the business, so instead of trying to sell, they’re transitioning their business to the next generation. That’s the top choice when it comes to exit strategies. Clearly, it’s the future of the channel.”

Unfortunately, almost 85 percent of family-owned businesses in the U.S. have no succession plans in place, even though they consider the topic their biggest challenge, according to a recent PricewaterhouseCoopers survey. To smooth the process for footwear retailers, NSRA introduced a Next Generation Leadership program eight years ago. Its centerpiece is an annual conference taught by experts in business transition. (See sidebar.)

First Steps

“Putting a plan for succession in place is really important,” says leadership consultant Diane Nettifee of Magis Ventures, a Minneapolis-based firm that specializes in helping organizations with successful transitions. “People often start too late. They underestimate how much time it takes to get the next generation ready.

“You need a development plan that supports the growth of people into their future roles. That’s how you make a transition feel consistent with what’s been good about a business and collaborative so that it helps the next generation of leaders to build on it,” adds Nettifee, who is working with Schuler Shoes on its transition plan.

Of course, up-and-comers aren’t the only ones who need support. “The more successful the retailer is, the more tied to their business they are,” says NSRA’s Schuyler. Those ties often make the older generation reluctant to pass the baton.

Such was the case for Adam Beck and his cousin, Julia Gomez-Beck, of Beck’s Shoes. When they were in their early twenties, both Becks knew they wanted to take over the family business, a California-based chain poised to celebrate its centennial next year.

“A lot of parents want to hold onto the business, but they’re doing themselves a huge injustice if they don’t start planning for succession,” says Adam Beck of Beck’s Shoes. “They’re going to hit a point where they’re fatigued. That’s no time to start training the next generation.”

Worse, he says, waiting doesn’t allow for unforeseen calamities. “I used to ask my uncle, ‘What if you’re not here tomorrow? What if there was an accident? What are we going to do about the business?’

“Julia and I were pretty aggressive about succession because we were introduced to the business at such a young age,” Beck explains. “We started working during the summer when we were ten and did every job from cleaning the bathrooms and mopping the floors to stocking shelves and checking in shipments all the way up through the retail process.”

The younger Becks started a dialogue with their dads and their grandfather, who were then co-owners, about the future of the family business seven years ago and enrolled in NSRA’s Next Generation Leadership Program shortly after it was introduced.

“The program was an eye-opener for us,” recalls Beck. “We thought our parents were behind the eight ball, but we soon realized they had really empowered us because they’d given us such an open, honest view of the business. We had a leg up because we knew what the balance sheet was. We knew the metrics. There were a lot of next geners who had never seen a P&L, never seen a balance sheet, didn’t know what their maintain margin was and had no idea what their parents made remuneration-wise. We knew all that, so succession for us was about looking at the things we were and weren’t good at and what we needed to do to be successful.”

The family officially transferred the business to Adam, now CEO, and Julia, now president and COO, two years ago. “We’ve been profitable 22 of the last 24 months,” says Beck, 37, of the enterprise, which now includes 12 stores, three shoemobile trucks and a thriving web business.

“Succession of any family business is extremely difficult, and the shoe business is difficult on top of that, so if you don’t have full transparency, the odds of taking it to the next generation are slim,” says Beck. “You need to know how to read a P&L and you need to know how to have strategic conversations with your family. You have to define what success will look like together. Is it a two percent annual increase in profits? Three percent? If you’re not all on the same page, it’s like going on a cross-country road trip with a destination in mind but without a map. We put a four-pronged approach into place for our succession: 1) Where have we been? 2) Where are we now? 3) Where do we want to be in the future? 4) How are we going to get there? Then we met at least once a month for a few hours to hash this stuff out over more than five years, and every time we ended a succession meeting, we scheduled another.” Another key, Beck says, is to have a good working relationship with your CPA, legal counsel, insurance broker and lawyer.

Letting Go

For Mark Farber of Mark Adrian Shoes—founded in Gloucester, MA, in 1975—passing the family business on to his son, Adam (the fifth generation in the family to become a shoe retailer) proved challenging but ultimately rewarding for both generations.

“Often parents pay lip service to the goal of transitioning the business without having intellectually and emotionally accepted the notion,” he says. “Most next geners I’ve met have aptitude and talent, but we parents are blindsided by our own emotional needs which block their path. It is neither fair nor best business practice to grudgingly concede to the next-gen that the transition will arrive some day. It needs to be accomplished as expeditiously as practical. It takes sacrifice and courage from parents to let go.”

When Adam decided to leave New York in 2014 with his wife, Sara, and asked Mark if he would train him to eventually assume ownership of the business, a laborious process involving everything from estate planning to family counseling followed. “Thanks to Adam’s motivational drive and business acumen, we truncated the transition time, and I retired in January 2017,” says Mark. “His success at navigating the rocky shoals of retail has exceeded my wildest expectations.”

The worst hurdle for Mark was simply accepting the change. “The biggest challenge of transitioning is for the parent to pack his parachute and prepare for landing. I didn’t do that, so my transition was a hard one, taking months to acclimate. Now I get such fulfillment watching all of my children succeed in their respective endeavors that I wouldn’t go back for anything,” says Mark, who now describes his role as “proud volunteer consigliere.”

Balancing Act

For help working through the wrenching emotional side of putting the family’s legacy into younger hands—as well as the practical aspects of the process—an impartial third-party expert can prove invaluable, as Farber, Beck and Schuler all discovered.

“An outside person can function as a safe confidant,” says consultant Nettifee. “People can say things to me that they wouldn’t feel safe saying to each other because they’d be afraid of hurting people’s feelings. A consultant gives you a place where you can be honest. The right consultant can also challenge you and help you grow in ways that can be hard for a family member to do.”

For the Schuler family, having a consultant is not only facilitating dialogue but helping to move the transition forward while protecting family ties. “The most important thing for us is that we come out of this transition with strong family relationships,” says Schuler, “but trying to balance not hurting people with doing what’s right for the business has been challenging. Our consultant talked one-on-one with each of us. Then she had me interview my kids and them interview me about our goals, dreams, fears and our vision for the company. It’s helped us to be transparent with each other and to work through problems.

“I’m not a very patient guy, but I’ve had to learn patience through this process,” he concedes. “It’s best if this doesn’t happen fast because you’ve got to make sure it’s right. You’ve got to make sure everyone’s on board, comfortable and happy. If you don’t get everyone to share their feelings, it can really backfire on you.”

Schuler’s advice? “Don’t give up. You might think you can’t transition your business because your kid doesn’t have the money or you don’t know how. But there is a way to make it work,” he says. “Pick a person who is passionate about the business. Find out if they really want to take it over. Those are the two most important ingredients. If you have those, make it clear to your son or daughter or kids that you really want to transition the business to them and remember that you can make it happen.”